In the opening scenes of the 2022 Oscar-nominated documentary To Kill a Tiger, subsistence farmer Ranjit is alone on screen. He sits, smiling, in front of a verdant landscape in Jharkhand, India, but he’s not admiring the vista: he’s gushing about his daughter, Kiran.

“We gave her so much love that there was nothing left to give,” he said, recounting her upbringing as a firstborn child. Then, his smile faltered. “As a father, I really regret that I was unable to protect her.”

Just a few months prior, 13-year-old Kiran was raped and beaten by three men. Sexual assault cases like Kiran’s weren’t new to their small village; in most cases, victims were married off to their rapists in an attempt to sweep the violent act under the rug. Ranjit, however, sought a different outcome for his daughter. The film follows his efforts to hold the three men accountable and achieve justice for Kiran, a feat that required uprooting decades-worth of the village’s customs and belief systems.

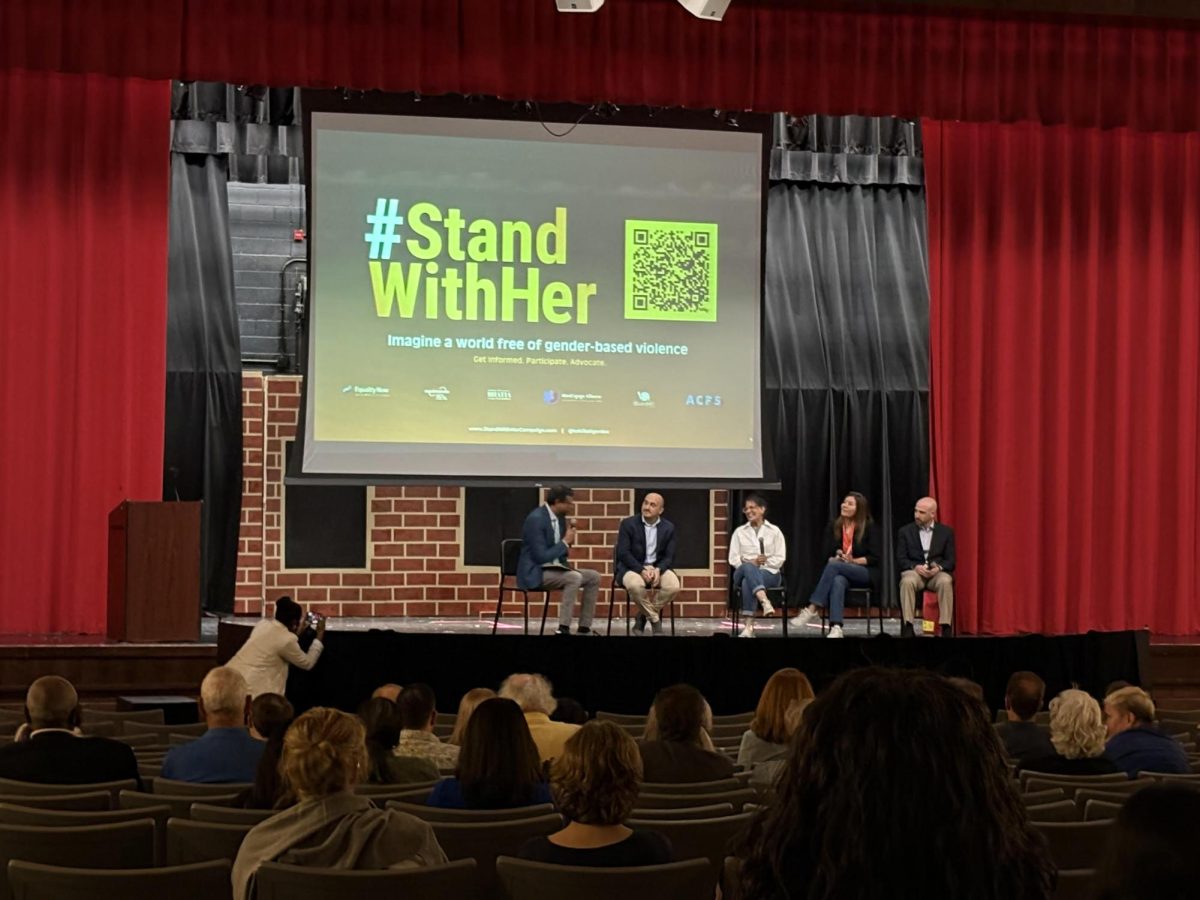

On Friday, May 2, ACHS hosted a screening of the film and a panel featuring its director Nisha Pahuja, who worked on the film for eight years before its release in 2022. Since then, the documentary has received an Academy Award nomination and is streaming on Netflix. The visit is part of the film’s #StandWithHer campaign which aims to promote gender justice through survivor empowerment, education and shifting of social narratives and encouragement of men and boys to engage in the movement.

The panel, moderated by author and surgeon Atul Gawande who was an executive producer of the film, also featured ACPS Family Engagement Social Worker Ana Bonilla and ACHS International Academy teacher Gabriel Ellias. Jose Campi, the director of communications and advocacy for Equimundo, a non-profit organization which aims to eliminate gender inequality and promote social justice, also joined them on the panel.

“It’s a film that shows us the worst that men can do, and at the same time it shows us the best that men can do,” said Campi.

Today, normalization of male aggression towards women is increasingly prevalent.

Social media figures like Andrew Tate preach male dominance and misogynistic ideals to their impressionable viewers. In an X post, a platform on which he has more than 10.7 million followers, Tate wrote that women should “bear responsibility for sexual assault.”

Just last October, 72-year-old french woman Gisèle Pelicot took the stand in court to testify being drugged by her husband and raped by dozens of men over the span of ten years.

“There is a power thing in there,” said Lytle Brent, an ACHS English teacher who organized the event. “This is a global issue– [Kiran’s story] is just a piece.”

Brent noted these gender-based violence can be boiled down to boys judging girls on their appearance, making inappropriate gestures, or making fun of girls in school locker rooms, often to “prove their masculinity.”

Katy Mejia Martel, an ACHS sophomore, can feel the weight of this underlying belligerence.

”Guys always judge you– by how you are, and how you’re built, and everything,” she said. “I just feel like I wanna change myself and then I just get choked up knowing after all the work [I] put it it’s still never enough.”

Numerous ACHS students are fighting gender-based aggression. Junior Peyton Turnbull helps lead the One Love club, which aims to spread awareness of toxic relationships and domestic violence among young adults.

Sharon Love founded the non-profit organization after her daughter, Yeardley Love, was murdered by her ex-boyfriend just weeks before her graduation at UVA.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 85 percent of domestic violence victims are female. However, Turnbull noted that almost all of One Love’s members are girls. “One of our main goals for next year is to get more boys involved,” she said. “So many aren’t educated [on domestic violence], and I think part of the reason boys are aggressive to girls is because they aren’t taught about these issues.”

”As humans and as men, we are wired to care– this is not something that needs to be taught,” Campi said. “That is something that we are born with, and if we lose it, [it’s] because of our environment, ’cause of the people that we had in our surroundings.”

“You know what the right thing is, we all know what the right thing is,” Pahuja said. “Human rights, equality: these are not negotiable.”

In addition to speaking on the panel, Pahuja also led presentations about the documentary and campaign throughout the school day, giving students the opportunity to learn more about the topic and ask questions.

“My eyes were definitely opened to gender-based violence and how it’s affected our world today,” said senior Seamus White, who attended one of the presentations. “Listening to [Pahuja] speak on the issues women face still in today’s world was an amazing call to action to me and everyone in the room.”

Campi added, “One of the biggest myths and lies of the human species is that we are meant to be independent.”

Later in the film, Kiran testifies in court. She recounts the event with precision and eloquence, her voice refusing to break. With the support and advocacy from other villagers, Kiran’s rapists were sentenced to 25 years in prison, the most extreme sexual assault sentence the village has ever seen.

“If our case stops these kinds of incidents from happening in our locality then I’ll consider it a sacrifice made by my daughter,” Ranjit said after the hearing. “There can be nothing greater in the world than sacrifice.”

Kiran is now 21-years-old and wants to be a police officer. Since the court hearing, there have been no reports of sexual assault in the village.

“ It is true that one person can kill a tiger,” Pahuja said, as she concluded the panel discussion. “But it is a lot easier if everyone helps.”