Several sources agreed to speak to Theogony on the condition of anonymity, as they feared for their job security. Altered names of anonymous sources appear with an asterisk upon first use and are always italicized.

Walking through the A-100 hallway of Alexandria City High School, Walter Caddel* was not expecting the course of his career to change anytime soon. Thirty minutes later, that assumption would be put into question. Beyond the doors of his administrator meeting, Caddel would find out that his position — along with the positions of 15 other deans and assistant principals — would be “restructured” next school year. In other words, they would all be required to reapply for their jobs.

After working in education for decades, and especially now in his position as an administrator, Caddel has become used to change. Instituting new practices and policies each year is common for schools, and ACHS is no exception. In the last three years, the school has dealt with numerous modifications, from a revamped bell schedule to the implementation of a sophisticated weapons detection system.

Considering such frequent adjustments, it may be easy to dismiss the restructuring of midlevel administrators as just another revision to how the school is run. But, for some, this change is more impactful than normal.

“I hope I don’t cry,” said Caddel in the first moments of an interview shortly after the decision was announced. “We come here, we show up every day, we give it our best, we care about the kids, we care about the school and we care about our colleagues … It feels awful.”

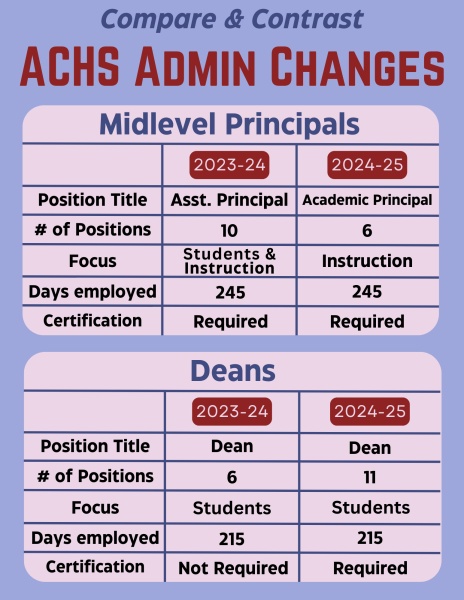

ACHS currently has 16 midlevel administrators who are responsible for everyday operations: 10 assistant principals and six deans. Next year, there will be 10 deans, six “academic principals” — one per academy — and one “lead administrator of school improvement” for the King Street and Minnie Howard campuses; there will also be one dean at the Chance For Change campus.

While all positions are on the same pay scale, deans will be employed for 215 days per year, compared to 245 days for academic principals and the school improvement administrator.

Additionally, all positions require administrative certification, which was not previously mandatory for deans. According to a source close to the situation, the district human resources department first communicated there would be a yearlong grace period to attain these credentials, but days before the jobs were posted, the period was changed to 90 days.

While deans will mainly focus on providing behavioral support to students, academic principals will coordinate and support interdisciplinary programs within one of the six new learning academies. They will also be responsible for overseeing a content area (for example, math or English) and evaluating teachers in that area.

[Read more about ACHS’s upcoming learning academies here.]

According to Executive Principal Alexander Duncan, who oversees all ACHS campuses, he and the “superintendent’s leadership team,” which consists of district chiefs, executive directors and Superintendent Melanie Kay-Wyatt, Ed.D., collaboratively made the decision. Duncan said the purpose of the restructuring is “to meet the needs of the upcoming launch of the academies.”

But some staff members said the effect of this change may stray from its intended purpose.

“It’s just absolutely crazy that they’re doing this,” said elective teacher Keera Johnston*. “It’s degrading if you think about it. These people applied for their positions, they’re doing the job and then the leadership says, ‘Oh wait, never mind.’”

“I think the administrators had no idea this was coming,” said English teacher Sarah Kiyak. Kiyak, who has taught at ACHS for the last 19 years, is leaving the school district at the end of the school year. She said that the restructuring was a major factor affecting her decision.

“My heart breaks for the administrators,” she said. “Their jobs and their livelihoods are at stake, and that’s really unfortunate. I think it’s incredibly unfair.”

A social studies teacher, Marie Matthews*, said she was expecting the change to occur.

“It was always going to be one academic principal over each academy,” Matthews said. “If you sort of read between the lines there, you understood that we were going from 10 to six assistant principals … Maybe they haven’t been telling the admin team that, and maybe that’s why it felt out of the blue.”

English teacher Alex Anton* questioned the timing of the change.

“It seems like a reckless move,” said Anton. “We’re facing a year that already has a lot of uncertainty, so I’m not sure why we would add to that uncertainty by ripping things up now.”

But one assistant principal, Robert Bowes, said he welcomes the decision.

“I think it’s a good thing,” he said. “Sometimes you have to change the way you do things. You can get caught in cycles of continuity. If there isn’t growth, then why are you staying on that same pattern?”

Bowes, who works at the Minnie Howard campus, has been an educator for 41 years; the last eight have been at ACHS.

“This is about innovating ourselves to get out there and think about things in a new way,” he said. “Are we helping the students? With this new model, I believe we are.”

Another midlevel administrator, Caleb Lee*, said he isn’t fully convinced.

“One thing I try not to do is speak from emotions, because sometimes emotions can drive different actions,” Lee said. “But I think this doesn’t bring stability, and I think that when you want to change a culture you have to have a plan.”

Critics are concerned that the decision could remove administrators with institutional knowledge, which they say is crucial for successfully operating the school during the opening of the new Minnie Howard campus. Six of the seven ACHS upper administrators began their positions since the beginning of last school year, and all of them were hired in 2021 or later. In contrast, six of the 10 assistant principals began their current positions since 2021. The other four have been at ACHS as long as 13 years.**

“The upper management of this school has been something of a revolving door over the last 15 years,” said teacher Jordan Payton*. “On the contrary, there are assistant principals who have been here for a pretty extensive period of time, who know the building, who know the kids, who are effective at leading their teams”

Payton, like Kiyak, is leaving Alexandria City Public Schools at the end of this school year, partially attributing his decision to the restructuring.

“This plan to make them reapply for their jobs is going to erase all that institutional memory,” he said.

“For the district to willingly slice away at the middle management that holds all of this institutional knowledge feels like a shot in our own feet,” said International Academy teacher Corrina Reamer.

Reamer, who has worked in other schools that were restructured, said she wishes the district had taken a milder course of action.

“Wiping the slate clean is like using a very blunt tool when we could do a better job with a scalpel,” she said. “I was disappointed to see such an un-nuanced approach to restructuring here when we just replaced almost the entire upper leadership team.”

Some teachers said this approach may have been used to remove administrators who were not meeting standards without dismissing them individually.

“Firing a school employee is very hard,” said Payton. “This is cleaner. It’s a policy. No one can claim discrimination or that there was no cause because it’s a universal policy.”

But Duncan said that was not the case.

“The decision was based on [adapting to] the academy structure,” he said. “The data has shown us that we as a school have got to find a different way to do what we do so that we can meet [the needs of] more young people … I worry about the 16 percent of students who are not graduating. That’s serious to me.”

In addition to its low graduation rates, ACHS has recently struggled to meet state averages for standardized test scores. Last school year, the majority of students taking the Virginia Standards of Learning exams for math, science or history did not pass. Only on the reading and writing SOL exams did students pass at a rate above state averages.

The school is currently “credited under conditions” by the Virginia Department of Education and is at the risk of losing accreditation entirely, although it is unclear when this would occur. If accreditation were lost, the state would take hold of ACHS and could subject it to extreme measures, including possible termination and re-hiring of all administrators and teachers. According to Carmen Sanders, the district executive director of instructional support, the restructuring may help reverse these worrying trends.

“When I think about school improvement … I think about the role of the current assistant principals,” said Sanders. “They have so much on their plate. They’re trying to both manage development and improvement in professional and teacher practices, and support students in multiple areas.”

With the restructuring, assistant/academic principals will focus solely on instructional support for teachers, and deans will revolve around student needs.

“I think the separation of the two jobs will help with maintaining focus and intentionality on the work to improve,” said Sanders.

Duncan said he believes the restructuring will help more students graduate, what he called the “purpose” of the school.

“When we as an institution keep that purpose at the forefront, will we have to make hard decisions sometimes?” he said. “Yes, we will. If that means we can advance student achievement, are there certain hard conversations we should stay away from because of how we feel certain individuals are going to struggle with those decisions? I can’t say that I believe that.”

Still, many staff members said the restructuring will not necessarily enhance student learning or experiences. Since support personnel — including counselors — will be attached to deans instead of assistant/academic principals next year, new relationships will have to be cultivated.

“It’s difficult and chaotic in this building a lot of the time, but one thing that makes it function for us is that we know the team we work with, and that team works well together,” said Caddel. “In taking that away, there’s just a lot of uncertainty.”

“This is too chaotic to do right now,” said Kiyak. “In five months, we’re about to open a new building. We don’t even know which teachers are going to be teaching in each building.”

“I’m not sure why we’re rushing everything,” said English teacher Katherine Bentley. “For next year, we should have just opened Minnie. Then we could try to add these academies. And then we can restructure based on academy. We’re trying to cram way too much into one year, and I think it’s going to be madness.”

Furthermore, some staff members said the decision has been detrimental to their trust in the school leadership.

“How do you trust someone when you see they’ll take an entire group of employees and just clean sweep them out?” said Reamer. “It affects the way I see the district and my interest in staying.”

“Yes,” Caddel said when asked if the relationship with his supervisors has been damaged. “If nothing else, because they have their jobs and we don’t.”

Some teachers also said they feel their perspectives on issues like the restructuring are often overlooked.

“Central Office and the upper administration continually say that they want to hear thoughts from teachers, that they want our opinions,” said Anton. “I’m in a lot of meetings where they ask me my opinion on little stuff. But big stuff, they just do what they want … That’s been demoralizing.”

During an online webinar for parents on April 18, Duncan described a more inclusive undertaking.

“Our staff has been very involved in this process,” he said, referring to the development of the academy model. “[They] have engaged in focus groups with our consultants on several different occasions, as well as campus-based working group committees … This whole process has been designed to not only include teacher voice, but to rely on [teachers] and their expertise.”

Anton said this did not happen for the administrative restructuring, something Duncan and Sanders later confirmed.

“They didn’t ask our opinion at all,” Anton said. “No one asked teachers about this restructuring. No one asked us about firing everyone.”

According to Sanders, staff engagement adhered to the precedent of previous restructurings in the district. The last time ACHS was restructured was in 2017, under the leadership of former Executive Principal Peter Balas.

“Through every restructuring I’ve seen implemented in ACPS, there has not been a voice given to the impacted staff, [including teachers],” Sanders said. “I’m curious because I’ve seen multiple restructurings and there was never this type of teacher response.”

The different reactions may be related to a perceived exclusion from relevant engagement on the academy model.

“We haven’t had a chance to really give feedback on how the academies work in a way that meaningfully moves the needle,” said Payton. “There have been feedback sessions, but nothing has really changed, despite many concerns being raised from every conceivable factor … Questions have been asked, and in many cases those questions were either kicked to other people, who didn’t know the answers, or were ignored.”

Payton said that a professional development day in March was specifically designated as a time for teachers to share their ideas, but it failed to pan out that way.

“Most of it was just us getting speeches about how great things are already working,” he said. “And then we were able to give feedback on a very narrow band of things, none of which included the academy structure.”

On the other hand, Bowes said he doesn’t mind how the decision was made.

“It’s not my job to be part of that planning process,” he said. “I’m not resistant to anything that my leaders tell me to do, because it’s their vision for what they want to accomplish … I have to respect the leaders who made those decisions.”

Even so, ACPS has created methods intended for staff engagement. One of these processes is an online survey where educators can submit questions regarding the High School Project. The questions are then answered by Duncan, Sanders and other Central Office staff in a shared spreadsheet. The spreadsheet, of which Theogony has obtained a copy, contains 123 total questions; just 38 of them have been answered or partially answered. The most recent answers were provided on March 11, according to an indicator in the spreadsheet.

When asked about the pending questions, Sanders said many of them are “redundant” and not questions that she “will be able to answer,” as she believes they are related to localized operational issues. She also said that “finding time to get into [the spreadsheet] again … will be of great importance for me within the next few weeks.”

A Theogony analysis of the spreadsheet found that 24 out of the 123 questions are redundant or duplicates and four pertain to specific operational issues.

Inside teacher working groups, which are designed as a vehicle for engagement, Matthews said staff perspectives can be brushed aside as well.

“We’ve been on the committees, we’ve put time and effort into them and then the administration has decided not to take our feedback into account,” said Matthews, who has been involved with planning the High School Project for years.

“It’s almost like you’re starting a relationship; you’re really excited, you’re building it up, you have lots of optimism and hope,” she said. “And then it’s just sort of undercut that, ‘No, we actually don’t care.’ That happens a lot in ACPS, and that’s why a lot of veteran teachers … are a little bit frustrated.”

Matthews said teachers would be more inclined to adapt to change if they were involved in major decisions instead of reliance on outside consulting firms. According to Sanders, a consulting “conglomerate” called Learner-Centered Collaborative was hired in 2023 for the High School Project. Teacher working groups had previously led planning stages of the project, but they were dismantled while the school system navigated more pressing issues like the Covid-19 pandemic.

“ACPS has a track record of inviting consultants to do things for us,” Matthews said. “These consultants are bringing great ideas, but they don’t know our student population … When it’s time for the implementation, it needs to be done by teachers.”

Matthews also said that when teachers try to share feedback, they can sometimes face backlash.

“There have been some situations where people have spoken out in meetings, and then we’ve heard they were taken into an administrator’s office and lectured to not be so negative,” she said. “[Administration and Central Office personnel] want everybody to fall in line; they don’t really want to hear the criticism.”

Other teachers concurred to varying magnitudes.

“There’s a culture of fear here,” said Johnston. “If you speak out, you get reprimanded for it.”

Johnston shared what she said is an example of this from 2021. According to Johnston, an administrator instructed a teacher to discuss their concerns only with upper administration and Central Office staff after that teacher replied-all to a schoolwide email thread to advocate for more transparency regarding conflict and drug use. Duncan told Theogony that he “can’t speak to other people’s experiences in the past” and “can only speak to the culture that I am trying to cultivate here.”

“You are driving your amazing teachers and administrators away,” Johnston said about the ACHS leadership team. “This is not a system where teachers who truly have a lot of passion for education want to be … How are we supposed to be great educators when we’re worried about X, Y and Z in the back of our heads? It’s all a domino effect.”

“I agree that there is a degree of a culture of fear among staff,” said Reamer. “I don’t think it’s universal, but I think it’s too widespread. It’s more widespread than any other school I’ve ever taught at. Blowing away the entire midlevel administration without cause certainly supports that fear and that way of thinking.”

Kiyak said this phenomenon is relatively new.

“I think that it started about 10 years ago as the communications program at Central Office started to revamp,” she said. “ACPS does its best to protect what’s going on and keep everything very insular … It’s a system that prefers silence and compliance.”

Other teachers said the abnormally large school population — with over 4,500 students across all campuses last year — results in staff feeling isolated by the bureaucracy.

“The school is so big that it’s hard to feel like you can go to someone in administration to talk to them,” said teacher Monica Jackson*. “They’re busy and I understand that, but it makes it difficult to feel comfortable going to someone that you don’t know more personally. I don’t necessarily think it’s fear.”

“This school is a small town; word gets around and people hold grudges,” said Anton. “I don’t think there’s generally a culture of fear, but I can see why people wouldn’t want to talk.”

Payton said he agreed with this analysis.

“There are ways people have of getting back at teachers,” he said. “Administrators can make your life miserable. You could be teaching four different classes; you could be given an insane student caseload; you could be pulled into every Individual Education Plan meeting under the sun as the teacher representative.”

“That’s one of the reasons it’s so important that people like [Assistant Principal] Maggie Tran exist,” Payton added. “They are administrators who work so hard to mitigate those outcomes and buoy them with helpful support and methods of making teachers’ lives easier, not harder.”

Whether or not a culture of fear exists, school staff are hesitant to speak publicly about the restructuring. Out of the 16 affected administrators, 10 declined to comment on the situation, with many saying they were applying to one of the new positions and believed speaking to Theogony could impact that process. Three could not be reached despite multiple requests for comment by email. Two others — in addition to four out of the seven teachers interviewed — spoke only on the condition of anonymity. Just one, Bowes, was willing to speak on the record.

If the restructuring decision was made to support students’ academic growth, a consequence has been an apparent impact on staff morale.

“I’ll probably reapply,” Caddel said. “But the other thing I say is, ‘Would you?’ I’m loyal to the school; I came here specifically over other schools. But if my loyalty isn’t being reciprocated, that isn’t a healthy relationship.”

“I’m not an individual unmoved, unbothered and unfazed by the feelings, the conditions and the perceptions of other people,” said Duncan. “In terms of my role as the Executive Principal, I needed to make [the restructuring] recommendation because that’s what my job is. In terms of my role as a human being, I wanted to make sure that this team received efficient, adequate and a number of supports from the division.”

“This is Duncan’s choice,” said Matthews. “When there are positions that are open, you bring in people that support your vision … As long as it’s what’s best for ACPS, I support it.”

But with so much instability in staff positions, Lee said he hopes that vision will not continue to change.

“We just have to do it right,” he said. “Keep everything student-centered and aligned with the goal — whatever that is — and make sure it’s not changing so much … We have to do better as a school.”

“My hope for the school community is that we can continue to find ways to create small communities, like the academies,” Caddel said. “But for next year, I hope they find the team that they want.

**The analysis of administrator starting dates does not include deans, as their position was created in 2023, or athletic staff.

This article is part one in our series, “Inside the High School Project,” which covers the controversial ACPS initiative that the district says intends to connect students across the four ACHS campuses. However, the initiative has received significant pushback from students, teachers and parents. Read part two of our series here, part three here, part four here, part five here, part six here, and a bonus part, which was published in the Alexandria Times over the summer, here. Theogony will continue our coverage through at least the end of the 2024-25 school year.

Comment your thoughts on the restructuring below.

Beth Coast • Apr 30, 2024 at 3:44 pm

Actually, teachers wouldn’t be fired first, Admin. would…. Went through this at JH and the Principal was let go…. FYI, that same Principal that we let go was Principal of the Year in Arlington. SMH….

james scheye • Apr 27, 2024 at 3:44 pm

Wow. Good digging James L.

Would like to see a direct response from ACPS leadership… maybe get something to consider for the -$20K in property tax I paid last year (no kids).

I am concerned to read teachers won’t give names. So WaPost.

I went to high school in Florida Panhandle. This sounds like the BS I read about in books now banned there.

Definite opportunity for room in improved student performance. Definite opportunity for school leadership, too.

I’ll finish: sounds like a David/Goliath story here. Administrators: grab some guts and start explaining.

Jim Scheye

DelRay/Alexandria

Whitney Patton • Apr 27, 2024 at 7:35 am

Excellent and courageous piece of journalism. Keep shining a light on the hard topics. It makes our community better!

Jackie Grabowski • Apr 26, 2024 at 3:28 pm

Kudos on bringing in so many perspectives. It is very concerning that there might be so much turnover of people with institutional knowledge right when the school is going through such a big change. And of course it must be very unsettling for the administrators to have their jobs up in the air. It will be too late to apply to other districts if they are squeezed out!

Raymond Espiritu • Apr 26, 2024 at 2:25 pm

Excellent reporting! And please continue to let us know the inner workings of the restructuring including the feedback from the teachers. As a parent of a student at ACPS HS I can say that, if parents and students are the “customers” then we know exactly where to go if we see policies that result in confusion and dismay.

We won’t go to the immediate employee (i.e. the teachers) we will go to upper management and complain.

Jennifer Hartenstine • Apr 26, 2024 at 2:22 pm

Excellent reporting and writing. Please keep updating this critical topic throughout next year. Keep shining light on this process!

Joel Finkelstein • Apr 26, 2024 at 2:05 pm Theogony Pick

I am incredibly impressed by the professional, deeply researched and enormously powerful piece of investigative journalism. It’s easy to forget that decisions like this are about real people’s lives, and you found a way to tell that story with humanity and clarity.

The ACHS community is so fortunate to have this level of student journalism. And if the administration is smart, they’ll appreciate that.