Peerawut Ruangsawasdi

Staff Writer

To Andrew Orzel, it seems like years since anyone in his government and economics classes expressed conservative ideas. That is concerning — given the diverse nature of the ACHS student body, one would expect a wide range of ideas discussed in a classroom setting.

I have Orzel for both government and economics. Although sometimes I don’t hold the most mainstream opinions — as I am sure many of my classmates don’t, either — I have never felt discouraged to occasionally share my “hot takes” when appropriate. So imagine my surprise when Orzel voiced concerns over conservative students’ reluctance to share their own takes, hot or cold.

However, I was even more startled to find that this problem is commonplace in our classrooms.

If it has truly been years since anyone expressed conservative ideas in classes, then there was a time when those ideas were present. What caused conservative students, in particular, to be more reticent in recent years?

I initially thought that the sole reason for this was that there were not many opportunities for debate in Orzel’s classes, which he acknowledged. He said the structure of the class is more geared towards relaying class materials according to the curriculum as opposed to opening up the class for discussions. While he welcomes discussions, he said the amount of content alone takes up a lot of class time.

However, the fact remains that whenever there is a discussion, according to numerous teachers, the student body generally speaks in viewpoint unity. But it’s not because they always agree — it’s because those who dissent are not speaking up.

If we were to find possible solutions, we must start by identifying the cause. Teachers and students alike seem to have different ideas about why this has become a problem.

“I certainly hope this isn’t the result of the environment I’ve created in my room, especially since many of my students don’t know my political beliefs,” Orzel said in a tweet. “I simply think they’re scared of their peers.”

Some teachers point to factors such as the specificity of the topic. “I don’t know if students are afraid to express themselves candidly, which may be part of the issue,” said a teacher who wished to remain anonymous. “I think students are more likely to express contrasting opinions on, say, the death penalty, than they are if the topic is political views in general.”

Some, like history teachers Erin Hudson and Tara Rougle, point to the uneasiness that students inherently feel when speaking to the class. Rougle said it could be beneficial if students prefer to share their opinions in writing, as it helps them to better formulate and defend their ideas.

These are all relevant contributing factors. But the growth of social media and its intertwinement with students’ daily lives has the potential to worsen this problem.

“[T]he most impactful [thing] is what anyone says can be recorded and exist forever on social media or on the internet,” said English teacher Alicia Cordero. “Someone can easily record, edit, and take what you say out of context, lacking nuance, to be used against you in many ways.”

“I largely blame social media,” replied History teacher Gabriel Elias to Orzel’s tweet. “I think we are adapting to it and not vice-versa.” But what makes going viral in the wrong way so terrifying seems to be its real life implications — the fear of retaliation from fellow students. For students who do not identify as politically liberal, that fear could even be more intensified in a school with a liberal environment.

At the start of each year, Orzel has his students take a Pew Research Center quiz that sorts them on the political spectrum. He is unable to see the results of individual students, but he can view the overall composition of his classes.

The results, according to Orzel, have usually demonstrated an overwhelming supermajority for liberal students.

“[I]t is usually only 10-15% who show up as conservative based on the results,” said Orzel. “I do think the liberal nature of the student body makes conservative students reluctant to share opinions and I assume students in schools with more ideological diversity are probably more [likely] to share their opinions.”

“I wouldn’t say I’m afraid as I have shared [my views] before,” said senior Xander Stickles, who identifies as conservative-leaning. He said that for some of his teachers and classmates, he “would rather not go through the trouble of someone disagreeing with me and trying to make me look like a bad person” because of his conservative views.

Another conservative student, who wished to remain anonymous, said if he says anything conservative, he instantly “become[s] the target for loads of hatred and ridicule.” He did not provide any specific examples, but said he has “lost numerous friends” because of differing political views.

Stickles believes social media can lead to widespread inaccurate representation of events, which might make students reluctant to share conservative ideas in class.

But conservative students are not the only ones feeling the effects of a lack in an energized conversational environment.

“[A]t times I do feel like I might have to [censor] myself because I don’t want to seem [too] aggressive or radical in my thinking, especially in majority White spaces,” student representative to the school board senior Sylvia Rahim, who is Black, said of her experience, “but even then I feel like because we live in such a liberal center I don’t feel like my own beliefs stray from the majority.”

She also said some students are afraid of losing friends or “social clout” if they state their “true beliefs.” She added that, because of social media, it is easy for things to go around and reach a vast number of people. She is “sure many students [are] afraid that if they share their own candid thoughts that stray from the majority they will be ostracized.”

“I would agree that some students are scared of their peers due to differences in views, which is not always the most productive,” said ACHS Young Democrats member Spencer Klaus, a junior, who said he is certain a few of his friends have differing beliefs and may find sharing them intimidating. “I would hope the environment built at school [allows] opinions to be shared while also respecting all students involved, but at some point you have to be able to have a discussion if you want to understand why people think the way they do.”

So, what could be done to incentivize students to share their ideas candidly?

“I never seemed to have a problem in encouraging my students to express themselves,” said former UCLA and Northeastern University Political Science professor Michael Dukakis, the Democratic presidential nominee in 1988. “I suspect that was largely because I emphasized class discussion, and I never thought straight lecturing made any sense. So my students expressed themselves clearly and forcefully, and their grades included a class participation factor.”

While mandating participation might result in more students speaking up, the ends don’t really justify the means, especially in a high school setting. Students are in the early stages of learning how to formulate and defend their arguments, basing them on facts and reason, while also being tolerant of other viewpoints.

“[S]tudents end up speaking to ‘check a box’ as opposed to actually wanting to share with the class,” said Orzel. “Speaking up in class also generates a lot of anxiety for many students and I don’t think students should be put in that position.”

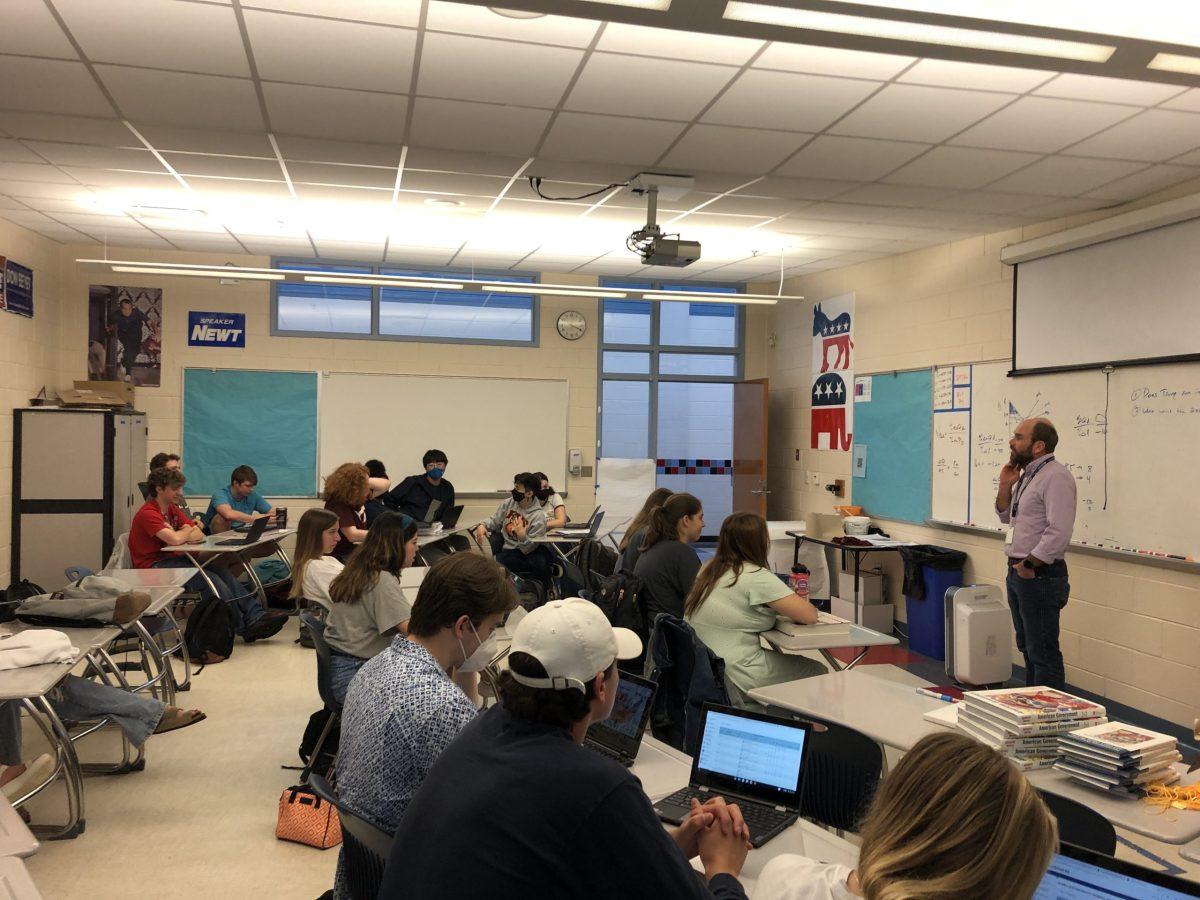

Andrew Orzel leading his class on a discussion about the 2024 election. Although 2024 is a long time from now, students were eager to participate and speculate on a peaceful Friday. Photo by Peerawut Ruangsawasdi.

What could be more helpful is telling students that there are many legitimate views on many topics. For their own personal political stances, however, teachers have different approaches to discussing them in class. Some believe that sharing them would lead to an uncomfortable environment, which could lead to students who disagree to not speak up. Other teachers think that it is impossible to be truly neutral.

“I try to ask if students want my opinion before I voice it,” said the previously mentioned anonymous teacher, “and make it clear that mine is not the only way of looking at things.”

Hudson said that, while she does not outright state her political views, she tries to “play devil’s advocate” to encourage students to approach issues critically.

In teaching international students, Elias believes that his job “is to give every side of every opinion, every theory, every viewpoint, every phase of historiography,” while also exercising empathy and understanding, including by sharing his own experiences. “I think in general, what gets people in trouble, in social media and in real life, is coming off too aggressive or insulting towards one group or another.”

For Orzel, he avoids sharing his political positions as much as possible because he thinks it creates a better classroom environment. He said he is well-aware that some teachers disagree. Some “tell their classes where they stand politically on the first day of school,” said Orzel, “so their students can determine whether or not what is being presented in class might be biased one way or the other.”

He said while he tries to avoid sharing his political positions, he is not afraid to “state the truth when one side is clearly correct and the other side is being dishonest.” He cited issues, like the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election, that appear to be political in nature, but really have to do with fact and fiction. He said that while there has been “far too much misinformation” in recent years, he “definitely would prefer to have an environment where students can openly express their views on a range of topics. There really are a lot of legitimate debates within the world of politics. … One side doesn’t have a monopoly on what is right and wrong when it comes to politics.”

English teacher Sarah Kiyak said she tries to be “transparent and honest” with her students, and that her political leanings are “probably obvious” from the novels and plays she chooses to teach, ones that “give voices to marginalized communities.” Kiyak was previously the faculty sponsor of ACHS Young Democrats.

Hudson said that while she often avoids sharing her political views, she thinks students tend to know where she stands on issues “simply by discussing our country’s history.” Similarly, English teacher Soukanya Lai-Sobchack said while she tries to avoid sharing her personal views to prevent discomfort and division in her classes, her liberal views “come out naturally” when discussing literature, as literature themes often “lend [themselves] to favor such concepts as democracy and human rights.”

Cordero said some teachers try not to share their views, citing ACPS policy against indoctrination. “It’s left to the interpretation of the students in the room as to whether or not teachers are simply engaging in basic discourse by expressing their beliefs or opinion,” said Cordero, “or if that teacher was ‘indoctrinating’ anyone. Too risky for many teachers to leave up for chance.”

Orzel referenced a similar policy, which states that teachers should not support political causes during working hours. “Several years ago, teachers were told to remove all overtly political content from their classrooms, including Black Lives Matter posters,” said Orzel. “The school has certainly moved away from that position and teachers seem to have a lot more freedom to display political content. I think the district has realized that there is a pretty fine line between supporting human rights and supporting political causes and has taken a more hands-off approach.”

There is a consensus of a need to acknowledge a wide array of views, especially of marginalized communities. But when it comes to sharing their own personal beliefs, I would defer to teachers to decide what approach is best for their classes. Personally, I appreciate Orzel’s efforts to remain neutral, and it has undoubtedly created a less intimidating environment. But whatever approach teachers take, I know all of them welcome different perspectives. Students should not think that sharing their views would somehow result in academic retaliation. It is nonsensical, not to mention that it would be a violation of ACPS policy.

Another helpful avenue would be class activities that are opportunities to practice civil discourse. Many teachers said they like Socratic seminars, which are big class discussions of a specific topic. “I love Socratic Seminars and guided discussions,” said Lai-Sobchak. “I find that students express themselves the most through writing. The more comfortable and safe they feel, the more genuine [their expressions are.]”

To be clear: no student should be forced to participate. Strengthening students’ right to speech goes both ways — making sure they can speak but also preserving their right to be silent. Sometimes, students benefit more from listening and thinking than speaking out of necessity.

This does not mean that they should be exempt from learning or doing the work, of course, but they should work out an alternative plan with their teachers.

“[I]t has to be the teacher’s responsibility to create an environment where a vast range of opinions and stances are encouraged. Students should never feel isolated or shamed for having a different opinion,” said Lai-Sobchak. “The difficult nature of controversial topics have to be taken into account … I have allowed students who are terrified of speaking to share their opinions after school or during lunch.”

“The best way to give everyone a chance to express themselves in ways they prefer is to offer multiple ways to do so,” Rougle said. “Anxiety might be induced by any of these [different] assignments in different students. I think as long as all assignments are not just one way of expression, that is good teaching and will meet the needs of all learners.”

“As teachers, our job is to differentiate instruction,” said Kiyak. “For example, if I am hosting a fish bowl/Socratic Seminar in my class, I know not everyone is going to feel comfortable sharing their opinions. Later in that unit, I’ll create another activity – like a Flipgrid or a written reflection – where students can share their perspectives with just me.”

She said giving students multiple ways to express their opinions is one way to make students more comfortable in sharing their viewpoints “no matter if it is conservative or liberal.”

“Socratic discussions were an essential part of all of my college courses,” said Cordero. “I’m not sure how they would work without a place for the exchange of differing views in a civil and educated way.”

By creating opportunities to facilitate healthy dialogue among students, students are given a chance to learn how to think critically and communicate civilly. In a school as diverse as ACHS, there would always be a chance for students to be exposed and engage in a fruitful conversation. Small steps leading to marginal progress that will accumulate overtime.

To students who want to speak up but are afraid to: If you are worried about your teachers, rest assured that no teacher would punish you for merely stating your opinions. In fact, they would love to hear from you. This is a perfect time to learn how to be better thinkers and better communicators, with guidance from your teachers. If you are worried about your peers, I am confident that if you share your thoughts civilly, your friends will understand.

To those who cut off ties with others with a different viewpoint: I truly do not believe, or hope, that many of you exist. But you should take into account that, on a lot of issues, you disagree with practically half of the population. It might not be wise to choose to alienate yourself from half the country. Engaging with those with differing viewpoints gives you an opportunity to learn — who knows, maybe you and your echo chamber have been wrong this whole time?

What helps ease tension is more civil discourse — not less. The student population is not a monolith. It would be egregious to assume so. Instead, we are a diverse community, not just in terms of what defines us — but also the ideas that we hold. I would urge everyone to take advantage of that fundamental quality.

Administrator Kelly Davis was exactly right when she encouraged students to “build that common bridge” with new people, as it provides a growth opportunity as you prepare yourself for post-high school life. And what better way to train students to build that bridge than to teach them to be more tolerant towards one another and to civilly participate in ACHS’ marketplace of ideas?

“[W]e need to learn how to LISTEN and communicate with one another, even when we have different points of view or don’t agree,” said Cordero. “We need a Civil Discourse course.”

Featured photo by Peerawut Ruangsawasdi

Peerawut Ruangsawasdi • May 30, 2022 at 12:45 am

It seems like there has been more of an effort to really ramp up community circles in classes, which I think could help — so far, most people say they haven’t been having them in their classes.